Meet Momotaro, the hero who was born from a peach. A mythical character with many popular legends and adventures.

Momotaro

Momotaro is a Japanese hero. His name translates as Peach Taro, a common Japanese male name, and is often translated as Peach Boy.

There is now a popular belief that Momotaro is a local hero of Okayama Prefecture, but this claim was invented in modern times and has not been accepted as consensus in academic circles.

1. Momotaro emerging from a peach

The present conventional form of the tale (Standard Type) can be summarized as follows:

Momotaro was born from a giant peach, which was found floating down the river by a childless old woman who was washing clothes there. The child explained that he had been given by the gods to be her son. The couple named him Momotaro, from momo (peach) and taro (eldest son in the family).

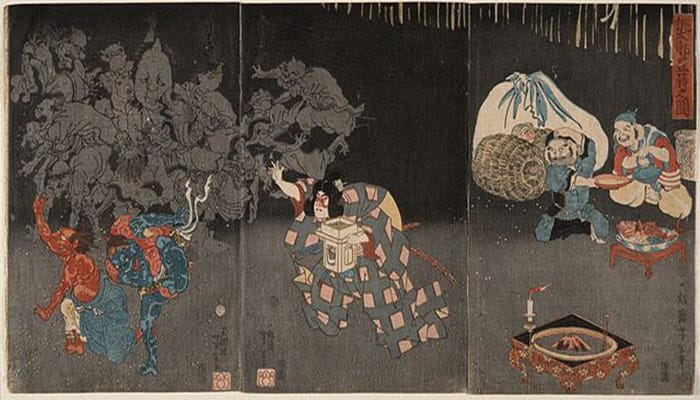

When he reached adolescence, Momotaro left his parents to fight a band of Oni (demons or ogres) who had taken refuge on their land, searching for them on the distant island where they lived (a place called Onigashima or “Demon Island”). This standard type of “Momotaro” was defined and popularized because it was printed in school textbooks during the Meiji period.

This is the result of the literary development of “Momotaro,” which had been written and printed by hand since the early Edo period in Meiji. A significant change is that in most examples of literature from the Edo period, Momotaro was not born from a peach, but was born naturally to the elderly couple who ate the peach and regained their youth.

Such subtypes are classified as the “rejuvenation” type kaishun-gata, while the current subtypes are called the “birth from fruit” type kasei-gata.

2. Development in literature

Although the oral version of the story may have emerged during the Muromachi period (1392-1573), it may not have been written down until the Edo period (1603-1867). [2] The oldest known works of Momotaro had been dated to the Genroku era (1688-1704) or perhaps earlier.

Edo period

These earliest texts from the Genroku era (e.g., Momotaro mukashigatari) are lost, but surviving examples from later dates, such as the reprint Saihan Momotaro mukashigatari (c.1777), preserve the earliest tradition and form the first group of texts (the most primitive) according to Koike Togoro. The late date of the reprint has sometimes led to it being classified as kibyoshi (“yellow cover”) or a later type of kusazoshi literature, but it should be correctly classified as akahon (“red book”) or early type.

A second group of texts, which Koike considered younger, includes the miniature akahon Mo taro, printed in Kyoho (1723). This miniature book is now considered the oldest copy of any written story of Momotaro.

Whether they belong to the first or second group, Edo period texts generally follow the same general plot as modern standard versions, but show certain differences in detail.

3. Birth of Peach

As noted above, in most books from the Edo period, the peach boy is not born from the peach, but from the woman who eats the peach and grows younger. Both the first and second groups consist entirely of “rejuvenation” types.

Examples of the “birth from the peach” type (such as the version in Takizawa Bakin’s 1811 essay Enseki zasshi “Miscelánea de Swallowstone”) are among the tales that have deviated the most, which Koike assigns to a third group of texts.

While the “birth from the peach” version has not been confirmed in earlier texts from the Edo period, a seductive sculpture dating from 1614 showed a man standing in the middle of a split peach. This supposed Momotar carved at the Kehi Shrine in Tsuruga, Fukui was lost during the air raids of 1945.

4. The age of Momotaro

It was noted that the protagonist Momotaro was being drawn progressively younger by artists over the years. In his subjective estimation, Momotaro appeared around the age of 30 until c. 1735, 25-ish until c. 1800, and 20-ish until the end of the Edo period in 1867.

Not all texts specify the age, but in the version by Kamo no Norikiyo (1798-1861), Hina no Ukegi Momotaro was 15 years and 6 months old when he set out on his expedition. And in Momotaro takara no kurairi (c. 1830-40), Momotaro was sixteen years old. The Momotaro in Iwaya Sazanami’s 1894 version was of a similar age (15) when he decided to go to Devil’s Island.

Researcher Namekawa Michio also noted the trend of Momotaro being depicted younger and younger, and called the phenomenon “age reduction trend” (teinenreika keiko).

5. Meiji period

After Japan abandoned the feudal system and entered the Meiji period, Iwaya Sazanami became a key figure in shaping the story of Momotaro and making it familiar to the Japanese masses. This was because he was not only the author of Momotaro stories in his commercially successful collections of folk tales, but also an important contributor to textbook versions.

The story “Momotaro” was first incorporated into nationalized textbooks for elementary schools by the Meiji government in 1887. It was subsequently omitted from the 1st edition of the National Language Reader or Kokugo tokuhon but reappeared from the 2nd edition through the 5th edition. It is generally accepted that the reader in the second edition of 1910 was de facto written by the author of the storybook Iwaya Sazanami, who joined the Ministry of Education as a non-permanent staff member in 1906.

The oldest texts took the punishment of the oni for granted and did not explain what crimes the oni had committed to deserve their punishment. But in Iwaya’s version, the ogres were explicitly declared to be evil beings who devoured the “poor people” and took the “plunder” from the land of the Emperor of Japan (Ozaki’s translation), thus morally justifying Momotaro.

It has been suggested that these ogres represented the Qing dynasty of China since the publication in the year the Sino-Japanese War broke out.

6. Oral variants

The story has some regional variations in oral narration.

In some variants, a red and white box is seen floating down the river, and when the red box is chosen to be retrieved, Momotaro is found inside. These may be a red box and a black box, or the box may contain a peach inside. These types are often seen in the northern parts of Japan (Tohoku and Hokuriku regions).

Or Momotaro may exhibit the lazy protagonist trait found in Netaro stories “Sleeping Boy.” These subtypes have been collected mainly in the Shikoku and Chügoku regions.

There are variations on Momotaro’s growth process; one is that he grew up to fulfill the elderly couple’s expectation that he would be a good boy. It is possible that the Momotaro who is a well-behaved child is more famous for teaching lessons to children.

In some versions of the story, Momotaro volunteered to help people by repelling demons, but in some stories the villagers or other people forced him to embark on a journey.

7. Claims as a local hero

Momotaro now enjoys a popular association with the city of Okayama or its prefecture, but this association was only created in the modern era. The publication of a book by Nanba Kinnosuke titled Momotaro no Shijitsu (1930), for example, helped the idea of Momotaro’s origins in Okayama to become more familiar.

Even so, as late as the pre-war period before World War II (1941-1945), Okayama was considered only the third contender behind two other regions known as Momotaro’s homeland.

8. Song of Momotaro

The popular children’s song about Momotaro titled Momotaro-san no Uta (The Song of Momotaro) was first published in 1911; the author of the lyrics is uncredited, while the melody was written by Teiichi Okano. The first two verses, with romanization and translation, are given below.

9. Plant

Echinocereus momotaro is a winter-hardy cactus from Japan.