Ixchel is the 16th-century name of the elderlyjaguar goddess of childbirth and medicine in ancient Mayan culture. She corresponds, more or less, to Toci Yoalticitl “Our grandmother, the night doctor,” an Aztec goddess of the earth who dwells in the steam bath, and is related to another Aztec goddess invoked at birth, namely Cihuacoatl (or Ilamatecuhtli). Ixchel corresponds to the Goddess O.

1. Identification

Referring to the early 16th century, the goddess Ixchel is called “the goddess of childbearing.” She is also mentioned as the goddess of medicine. During the month of Zip, the religious festival, the goddess Ixchel was celebrated by doctors and shamans (sorcerers), and divination stones and medicine packages containing small idols of “the goddess of medicine whom they called Ixchel” were presented.

In the Ritual of the Bacabs, the goddess Ixchel is called “grandmother.” Taken together, the two main qualities of the goddess (childbirth and healing) suggest an analogy with the ancient Aztec goddess of midwifery, Toci Yoalticitl. The goddess Ixchel was already known to the classical Maya. As Taube has shown, she corresponds to the goddess O in the Dresden Codex, an elderly woman with jaguar ears.

A crucial piece of evidence in his argument is the so-called “Birth Vase,” a classic Maya container depicting a birth presided over by several elderly women, led by an ancient jaguar goddess, the Codex O goddess; all have weaving implements in their headdresses. In another classic Maya vase, the goddess O is shown acting as a doctor, further confirming her identity as Ixchel.

The combination of the goddess Ixchel with several elderly midwives on the Birth Vase is reminiscent of the Tzutujilla assembly of midwife goddesses called “female ladies,” the most powerful of whom is described as particularly fearsome.

2. Meaning of the name

The name Ixchel was used in Yucatan in the 16th century and among the Poqom in Baja Verapaz. Its meaning is uncertain. Assuming that the name originated in Yucatan, chel could mean “rainbow.” Its glyphic names in the codices (postclassical) have two basic forms, one is a prefix with the primary meaning of “red” (chak) followed by a portrait glyph (“pictogram”), the other is logosyllabic. The glyph for the classical name of Ix Chel has not yet been identified.

It is quite possible that several names were in use to refer to the goddess, and these did not necessarily have to include her Yucatec name and Poqom. The name is now generally presented as “Chak Chel.” The designation “Red Goddess” seems to have a complement in the designation of the young goddess as “White Goddess.”

3. Ixchel and the moon

In ancient times, storytellers speculated that Ixchel was a goddess similar to the classical Maya moon deity, with the moon society corresponding to fertility and multiplication. However, iconographically, such an equivalence was controversial, given what is believed to be the classical Maya moon deity.

On the other hand, the waning moon is often called “Our Grandmother,” and, logically, Ixchel could have represented this particular phase of the moon. Associated with declining fertility and the eventual dryness of old age. Her code attribute of an inverted jar could then refer to the waning moon jar that is emptying. The equation of the triad of sister, mother, and grandmother with the three basic phases of the moon seems to be quite common among cultures around the world.

4. Ixchel as a goddess of the earth and war

An intertwined snake serves as Ixchel’s headdress, crossed bones may adorn her skirt, and instead of human hands and feet, she sometimes has claws. Very similar features are found with the Aztec goddesses of the earth, from whom midwives invoked Tlaltecuhtli, Toci, and Cihuacoatl.

More specifically, the jaguar goddess Ixchel could be conceived as a warrior, with an open mouth suggesting cannibalism, thus showing her affinity with Cihuacoatl Yaocihuatl, “Woman of War.” This manifestation of Cihuacoatl was always hungry for new victims, just as her midwife manifestation helped produce new babies seen as captives.

5. Ixchel as a goddess of rain

In the Dresden Codex, the goddess O is found in almanacs dedicated to the rain deities or Chaacs, and she often turns a jar of water upside down. Originally, her emptying of the water jug replicated the vomiting of water by a celestial dragon. Although this scene is usually understood as the Flood that brings about the end of the world and the end of the year, it could also represent the beginning of the rainy season.

The image of the jar filled with rainwater may represent a pregnant womb containing amniotic fluid; turning the jug would be equivalent to giving birth.

6. Mythology

Ixchel appears in a Verapaz myth related to Las Casas, according to which she and her husband, Itzamna, had thirteen children, two of whom created the sky and the earth and everything in it. No other myths about Ixchel have been preserved. However, her mythology may once have focused on the sweat bath, the place where Mayan mothers used to go before and after giving birth. As noted above, Ixchel’s Aztec counterpart as patroness of midwifery, Toci, was also the goddess of the sweat bath.

In the myths of Oaxaca, the elderly adoptive mother of the brothers Sun and Moon is eventually imprisoned in a steam bath to become their patron deity. Several Mayan myths have aged the goddesses who end up in the same place, particularly the Cakchiquel and Tzutujil grandmother of the Sun and Moon, called Batzbal in Tzutujil. On the other hand, in the Qeqchi myth of Sun and Moon, an elderly Mayan goddess who would otherwise seem to be closely related to the Old Adoptive Mother of Oaxaca, does not appear to be connected to the sweat bath.

7. Cult of Ixchel

In the early 16th century, Mayan women seeking to ensure a fruitful marriage traveled to the sanctuary of Ixchel on the island of Cozumel, the most important pilgrimage site after Chichen Itza, off the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula. There, a priest hidden in a large statue would give oracles.

North of Cozumel is a much smaller island named by its Spanish discoverer, Hernández de Córdoba, “Isla de Mujeres” (Island of Women) “because of the idols he found there, of the goddesses of the country, Ixchel. On the other side of the peninsula, the city of Chontal, in the province of Acalan (Itzamkanac), worshipped Ixchel as one of its main deities.

One of the coastal settlements of Acalan was called Tixchel, “In the place of Ixchel.” The Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés tells us about another place in Acalan where no one is married. Young women were sacrificed to a goddess in whom “they had great faith and hope,” possibly Ixchel again.

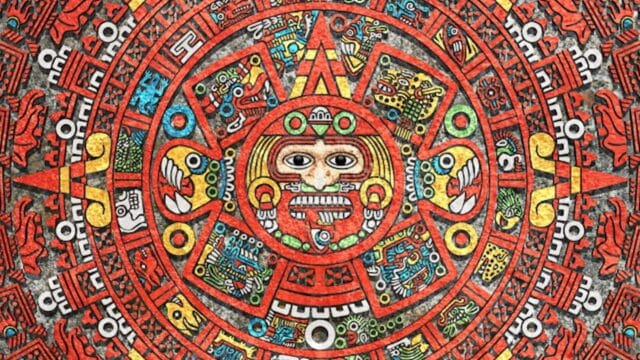

8. Appearance of Ixchel

According to Spanish colonial records, the Maya believed that the moon goddess roamed the sky, and when she was not in the sky, she was said to live in cenotes (natural sinkholes filled with water). When the waning moon reappeared in the east, people made a pilgrimage to the Ixchel sanctuary in Cozumel.

In the traditional pantheon of Maya gods and goddesses, Ixchel has two aspects, that of a sensual young woman and a very old woman. However, that pantheon was constructed by archaeologists and historians based on a wide variety of sources, including iconography, oral history, and historical records. Over decades of research, the Maya have often debated whether they have incorrectly combined two female deities (goddess L and goddess O) into one moon goddess.

Goddess I

The main aspect of Goddess I is as a young, beautiful, and frankly sexy wife, and she is sometimes associated with references to the crescent moon and rabbits, a pan-Mesoamerican reference to the moon. (In fact, many cultures see a rabbit in the face of the moon, but that’s another story.) She often appears with a beak-like appendage protruding from her upper lip.

Goddess L

Goddess I is known as Ixik Kab (“lady of the earth”) or Ixik Uh (“lady of the moon”) in the Mayan books known as the Madrid and Dresden codices, and in the Madrid codex she appears as a young and aged version. She is the goddess who presides over marriage, human fertility, and physical love. Her other names include Ix Kanab (“Son of the Lady of the Seas”) and Ix Tan Dz onot (“Son of She in the Middle of the Cenote”).

Ixik Kab is associated with weaving in the postclassic period, and the aged form of Ixik Kab is often shown weaving and wearing a pair of horn-shaped items on her head that probably represent spindles.

Goddess O

The goddess O, on the other hand, is a powerful old woman identified not only with birth and creation, but also with death and world destruction. If these are different goddesses and not aspects of the same goddess, it is very likely that the goddess O is the Ixchel of ethnographic reports. The goddess O is married to Itzamna and is therefore one of the two “creator gods” in Mayan origin myths.

The goddess O has a series of phonetic names that include Chac Chel (“Red Bird” or “Great End”). The goddess O is depicted with a red body, and sometimes with feline features such as jaguar claws and fangs; she sometimes wears a skirt marked with crossed bones and other symbols of death. She is closely identified with the Mayan rain god Chaac (God B) and is often depicted with pouring water or images of flooding.

The fact that the name of the Goddess O means that both rainbows and destruction can come as a surprise, but unlike in our Western society, rainbows are not good omens for the Maya, but bad ones, the “flatulence of demons” that rise from dry wells. Chac Chel is associated with weaving, fabric production, and spiders; with water, healing, divination, and destruction; and with childbirth and childbirth.

9. Four goddesses?

The moon goddess of Mayan mythology may actually have many more aspects. The first Spanish travelers in the early 16th century recognized that there was a flourishing religious practice among the Maya dedicated to “aixchel” or “yschel.” Local men denied knowing the meaning of the goddess, but she was a deity of the Chontal, Manche Chol, Yucatec, and Pocomchi groups in the early colonial period.

Ixchel was one of four related goddesses worshipped on the islands of Cozumel and Isla de Mujeres: Ixchel, IxChebal Yax, Ix Hunie, and Ix Hunieta. Mayan women made pilgrimages to their temples on the island of Cozumel and placed their idols under their beds, asking for help.

10. The Oracle of Ixchel

According to various historical records, during the Spanish colonial period, there was a life-size ceramic statue known as the Oracle of Ixchel located on the island of Cozumel. It is said that the oracle in Cozumel was consulted during the founding of new settlements and in times of war.

It was said that pilgrims followed sacbe from as far away as Tabasco, Xicalango, Champotón, and Campeche to worship the goddess. The Mayan pilgrimage route crossed Yucatán from west to east, mirroring the path of the moon across the sky. Colonial dictionaries report that the pilgrims were known as hula and the priests were Aj Kin. The Aj Kin posed the pilgrims’ questions to the statue and, in exchange for offerings of copal incense, fruit, and sacrifices of birds and dogs, reported the answers in the voice of the oracle.

Francisco de López de Gomara (chaplain to Hernán Cortés) described the sanctuary on the island of Cozumel as a square tower, wide at the base, and he walked around it. The upper half was erect, and at the top there was a niche with a thatched roof and four openings or windows. Inside this space was a large hollow clay image, baked, attached to the wall with lime plaster: this was the image of the moon goddess Ixchel.

11. Finding the Oracle

There are several temples located near the cenotes at the Mayan sites of San Gervasio, Miramar, and El Caracol on the island of Cozumel. One that has been identified as a plausible location for the oracle’s sanctuary is the Ka na Nah or Great House at San Gervasio.

San Gervasio was an administrative and ceremonial center in Cozumel, and had three complexes of five groups of buildings, all connected by sacbe. Ka na Nah (Structure C22-41) was part of one of these complexes, consisting of a small pyramid five meters (16 feet) high with a square plan of four stepped tiers and a main stairway bordered by a railing.

Mexican archaeologist Jesús Galindo Trejo argues that the Ka na Nah pyramid appears to be aligned with the greatest lunar standstill when the moon sets at its extreme point on the horizon. The connection of C22-41 as a contender for the Oracle of Ixchel was first presented by American archaeologists David Freidel and Jeremy Sabloff in 1984.

So who was Ixchel?

American archaeologist Traci Ardren has argued that the identification of Ixchel as a unique moon goddess combining female sexuality and traditional gender roles of fertility comes directly from the minds of the earliest scholars who studied her. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ardren says, male Western scholars incorporated their own biases about women and their roles in society into their theories about Maya myths.

These days, Ixchel’s reputed fertility and beauty have been appropriated by various non-specialists, commercial properties, and New Age religions, but as Ardren quotes Stephanie Moser, it is dangerous for archaeologists to assume that we are the only people who can create meaning from the past.