Cintamani is a jewel that grants all wishes, both in Hindu and Buddhist traditions, and some say it is the equivalent of the philosopher’s stone in Western alchemy. It is one of several images of Mani Jewel found in Buddhist scriptures.

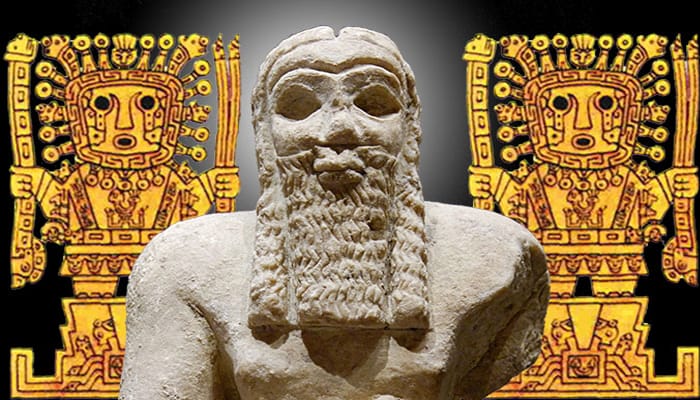

One such solid gold statue was found in Cuzco; it stood 4 feet tall. The figures’ right arms were raised and their fists were closed, except for the thumb and index finger. It was eternal and created everything, including other deities. The three main gods under Viracocha were Inti (the Sun), Illapa (thunder) or the god of time, and Mamaquilla (the Moon).

There are many legends about Viracocha. One legend says that Inti was his son and Mama Quilla and Pachamaam were his daughters. According to this legend, he created a flood and destroyed the people around Lake Titicaca. He saved only Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo so that they could bring civilization to the world. Later, Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo founded the Inca civilization.

1. Content

Considered the supreme creator god of the Incas, Viracocha (also known as Huiracocha, Wiraqocha, and Wiro Qocha) was revered as the patriarchal god in pre-Inca Peru and Inca pantheism. His name was so sacred that it was rarely spoken aloud, but was replaced by others, such as Ilya (light), Ticci (beginning), and Wiraqocha Pacayacaciq (instructor).

This reverence is similar to other religious traditions, including Judaism, in which the name of God is rarely spoken, but is replaced with words such as Adonai, Hashem, or Yahweh. Viracocha is part of the rich multicultural and multireligious lineage and cosmology of the gods of creation myths, from Allah to Pangu to Shiva.

A brief sample of creation myth texts reveals a similarity in the Bible in the first book of the Old Testament (Genesis 1:1), which says, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.”

“When heaven and earth began, three deities came into existence: the Master Spirit of the Center of Heaven, the Spirit that Produces Marvelously in August, and the Ancestor that Produces Marvelously in the Divine. These three were invisible. The earth was young then, and the earth floated like oil, and from it sprouted shoots of cane.”

“In the beginning, there was chaos, the abyss. From it emerged for the first time Gaia, the earth, which is the foundation of everything. Then came Tartarus, the depth of the Earth where condemned dead souls go to their punishment, and Eros, the love that overwhelms bodies and minds, and Erebos, darkness, and Nyx, night. Erebos and Nyx made love, and from their union came Aether, air, and Hemera, day.” “(Gaia,” Theogony)

These texts, like most creation myths (regardless of their origin), focus on the common idea of a powerful deity or deities who create what we understand to be life and all its aspects. The legendary Viracocha, the God of Creation in ancient South American cultures and a symbol of the human capacity to create, destroy, and rebuild, is firmly rooted in the themes of creation mythology.

2. The Legend of Viracocha

The legend tells us that a primordial Viracocha emerged from Lake Titicaca, one of the most beautiful and spiritual bodies of water in the world and located next to Tiwanaku, the epicenter of ancient pre-Hispanic South American culture, where spiritual secrets were believed to be found in the Andes.

Viracocha is closely connected to the ocean and all water, and to the creation of two races of people: a race of giants who were eventually destroyed by their creator, some of whom were turned into enormous stones that are believed to still be present in Tiwanaku.

He reemerged from Lake Titicaca to create the race most associated with humans as we understand them today. Satisfied with his efforts, Viracocha embarked on an odyssey to spread his form of gospel: civilization, from the arts to agriculture, language, and the aspects of humanity shared across cultures and beliefs.

Although written language was not part of Inca culture, rich oral and non-linguistic modes of record-keeping sustained the mythology surrounding Viracocha as the supreme creator of all things.

Today, the various structures and monoliths, including the architecturally impressive Sun Gate, are well-visited ruins that bear witness to the powerful civilization that reached its peak between 500 and 900 AD and profoundly influenced Inca culture.

Viracocha creates the world

In the beginning, there was darkness and nothing existed. Viracocha the Creator emerged from the waters of Lake Titicaca and created the earth and the sky before returning to the lake. He also created a race of people—in some versions of the story, they were giants. These people and their leaders displeased Viracocha, so he emerged from the lake again and flooded the world to destroy them. He also turned some of the men into stones.

People are made and come forward

Then Viracocha caused men to populate the different areas and regions of the world. He created people, but left them inside the Earth. The Inca referred to the first men as Vari Viracocharuna. Viracocha then created another group of men, also called viracochas.

He spoke to these Viracochas and made them remember the different characteristics of the peoples who would populate the world. Then he sent all the Viracochas away except for two. These Viracochas went to the caves, streams, rivers, and waterfalls of the earth, every place where Viracocha had determined that people would leave the Earth.

The Viracochas spoke to the people in these places, telling them that the time had come for them to leave the Earth. The people left and populated the earth. Viracocha and the people of Cañas:

Viracocha then spoke to the two who had remained. He sent one to the east to the region called Andesuyo and the other to the west to Condesuyo. Their mission, like the other Viracochas, was to awaken the people and tell them their stories. Viracocha himself set off for the city of Cuzco.

As he advanced, he awakened the people who were on his path but had not yet been awakened. On the way to Cuzco, he went to the province of Cacha and awakened the people of Cañas, who emerged from the Earth but did not recognize Viracocha.

They attacked him, and he rained fire on a nearby mountain. The Cañas threw themselves at his feet, and he forgave them.

Viracocha founds Cuzco and walks on the sea

Viracocha continued on to Urcos, where he sat on the high mountain and gave the people a special statue. Then Viracocha founded the city of Cuzco. There he called the Orejones from the Earth: these “big ears” (large gold discs were placed on their earlobes) would become the lords and ruling class of Cuzco.

Viracocha also gave his name to Cuzco. Once this was done, he walked towards the sea, awakening the people as he went. When he reached the ocean, the other Viracochas were waiting for him. Together they crossed the ocean after giving their people one last piece of advice: beware of false men who would come and say they were the Viracochas who had returned.

3. Variations of the myth:

Due to the number of cultures conquered, the means of preserving history, and the unreliable Spaniards who first wrote it down, there are several variations of the myth. For example, Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa (1532-1592) tells a legend of the Cañari people (who lived south of Quito) in which two brothers escaped Viracocha’s destructive flood by climbing a mountain. After the waters receded, they built a hut.

One day, they came home to find food and drink for themselves. This happened several times, so one day they hid and saw two Cañari women bring food. The brothers came out of their hiding place, but the women fled. The men then prayed to Viracocha, asking him to send the women back. Viracocha granted their wish, and the women returned: legend has it that all Cañari people are descended from these four villages.

Father Bernabé Cobo (1582-1657) tells the same story in more detail.

4. The Incas and Civilization

The Incas were a powerful culture in South America from 1500-1550, known as the Spanish “Age of Conquest.” Rich in culture and complex in its systems, the Inca empire expanded from what is now Colombia to Chile.

The significance of the Viracocha creation mythology for Inca civilization says a lot about the culture, which despite being engaged in conquest, was surprisingly inclusive. The beliefs of a rival tribe, following a victorious conquest, were adopted by the Incas.

Furthermore, enemies were allowed to keep their religious traditions, in stark contrast to the period of Spanish rule, which required conversion on pain of death.

The Incas, as a deeply spiritual people, professed a religion built on an interconnected group of deities, with Viracocha as the most revered and powerful. The stars and constellations were worshipped as celestial animals, and places and objects, or huacas, were seen as inhabited by the divine, becoming sacred sites.

5. The meaning of Viracocha today

The story of Viracocha begins and ends with water. He emerged from Lake Titicaca, then walked across the Pacific Ocean, promising to return one day. The messianic promise of return, as well as the connection to the waters of the tides, reverberates in today’s culture.

For many, the myth of Viracocha’s creation continues to resonate, from his loving investment in humanity to his promise to return, representing hope, compassion, and ultimately the goodness and capacity of our species.

6. Viracocha and the legendary origins of the Inca

The Incas of the Andean region of South America had a complete creation myth involving Viracocha, their Creator God. According to legend, Viracocha emerged from Lake Titicaca and created all things in the world, including man, before sailing to the Pacific Ocean.

The Inca Culture

The Inca culture of western South America was one of the richest and most culturally complex societies encountered by the Spanish during the Age of Conquest (1500-1550). The Inca ruled a powerful empire that stretched from present-day Colombia to Chile.

They had developed a complex society ruled by an emperor in the city of Cuzco. Their religion centered on a small pantheon of gods including Viracocha, the Creator, Inti, the Sun, and Chuqui Illa, the Thunder. The constellations in the night sky were revered as special celestial animals.

They also worshipped huacas: places and things that were somehow extraordinary, such as a cave, a waterfall, a river, or even a rock that had an interesting shape.

The Inca Archives and Spanish Chroniclers:

It is important to note that although the Incas did not have writing, they had a sophisticated system of record keeping. They had a whole class of individuals whose duty was to remember oral histories, passed down from generation to generation. They also had quipus, sets of knotted strings that were remarkably accurate, especially when it came to numbers.

It was through these means that the Inca creation myth was perpetuated. After the conquest, several Spanish chroniclers wrote down the creation myths they heard. Although they represent a valuable source, the Spaniards were far from impartial: they thought they were hearing dangerous heresies and judged the information accordingly.

Therefore, there are several different versions of the Inca creation myth: what follows is a compilation of the main points on which the chroniclers agree.

7. Importance of the Inca Creation Myth

This creation myth was very important to the Incas. The places where people emerged from the Earth, such as waterfalls, caves, and springs, were revered as huacas—special places inhabited by a kind of semi-divine spirit.

At the site of Cacha, where Viracocha supposedly summoned fire against the belligerent Cañas people, the Inca built a shrine and revered it as a huaca. At Urcos, where Viracocha had sat and given a statue to the people, they also built a shrine.

They made a huge gold bench to hold the statue. Francisco Pizarro would later claim the bench as part of his share of the spoils of Cuzco. The nature of the Inca religion was inclusive when it came to conquered cultures.

When they conquered and subjugated a rival tribe, they incorporated that tribe’s beliefs into their religion (albeit in a position inferior to their own gods and beliefs). This inclusive philosophy contrasts with that of the Spanish, who imposed Christianity on the conquered Inca while attempting to eradicate all vestiges of the native religion.

Because the Incas allowed their vassals to maintain their religious culture (to a certain extent), there were several creation stories at the time of the conquest, as noted by Father Bernabé Cobo:

“As for who these people may have been and where they escaped from that great flood, they tell thousands of absurd stories. Each nation claims for itself the honor of having been the first people and that all others came from them.”

However, legends of different origins have some elements in common, and Viracocha was universally revered in Inca lands as the creator. Today, the traditional Quechua people of South America—the descendants of the Incas—know this legend and others, but most have converted to Christianity and no longer believe in these legends in a religious sense.